-

Equine Endocrinology Group. Recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of pituitary pars intermedia dysfunction (PPID). July 2020. Available at: https://sites.tufts.edu/equineendogroup/ (accessed March 2022).

-

Ireland and McGowan, et al. Vet J. 2018;235:22–33.

-

McGowan TW, et al. Equine Vet J. 2013;45(1):74–79. 4. McFarlane D.

-

Durham AE, et al. Equine Vet Educ. 2014;26(4):216–223.

-

Carmalt JL, et al. Can J Vet Res. 2017;81:261–269.

Pituitary Pars Intermedia Dysfunction: PPID

What is PPID?

A disease that occurs mainly in older horses and ponies.

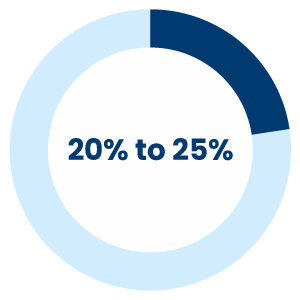

Equine Cushing’s disease, nowadays better referred to as PPID, is a disease that occurs mainly in older horses and ponies. PPID occurs in around 20% to 25% of horses aged 15 years or older, but it can also manifest at a younger age2,3.

Hormonal Dysregulation

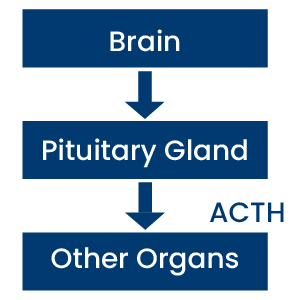

The pituitary gland is located at the base of the brain and produces hormones, like ACTH, in response to brain signals.

In PPID, the normal mechanisms which control hormone production by the pituitary gland are damaged. There is excessive production of the normal hormones (ACTH) from the pituitary. This hormonal overproduction then affects the whole horse's body.

What are the signs of PPID?

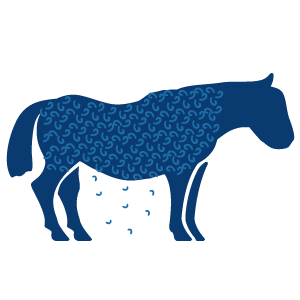

Your horse can show a wide range of clinical signs when suffering from PPID. The early clinical signs of PPID can often be overlooked or put down to old age at first.

These are:

- Development of a pot-belly appearance and loss of topline over the back, both associated with reduced muscle mass.

- Abnormal fat distribution (bulging of the hollow above the eyes).

Other signs develop as the disease progresses:

- Development of a long, curly coat.

- Delayed or incomplete shedding of coat.

A more serious clinical sign is susceptibility to infections (including parasitic infections i.e. worms).The most worrying clinical sign of PPID is laminitis. Horses and ponies should have their feet regularly examined/checked by a farrier.

Other signs include:

Abnormal Sweating

Excessive drinking and urination

Lethargy

Infertility

When you see any of these signs, consult your veterinarian.

How is PPID diagnosed?

PPID should be diagnosed based on clinical signs and diagnostic testing1.

The most commonly used test to diagnose PPID is a blood sample to measure the level of the hormone ACTH. As seasons impacts ACTH blood concentration, this test should preferably be performed in autumn. If the test is not fully conclusive, it should be repeated, or, in some horses, your vet would ask for additional tests, like TRH stimulation.

And in some cases clinical signs alone may be sufficient for a diagnosis, for instance the appearance of a long curly hair coat. Early diagnosis and treatment of PPID are essential to help improve a horse’s quality of life and prevent secondary illnesses such as recurrent infection and laminitis1,4,5.

How can PPID be managed?

PPID is a life-long condition that requires ongoing, daily treatment, commonly with oral pergolide, and supportive care.5

Medication

Every horse is unique. A dose of pergolide that is working perfectly on one horse might give different results on another one. Based on your horse’s size and response to therapy, the dose of pergolide should be adjusted to achieve an optimal treatment response. Regular assessment of the dosage is recommended (every 4 to 6 weeks until stabilisation or improvement of clinical signs) to achieve the best treatment outcome with the least side effects.1,4

Supportive care

Alongside medication and depending on what you see on your horse the following supportive care should be given:

- To keep your horse comfortable and dry, hair should be kept short all year round. When temperatures lower do not forget rugging.

- Because of the effects of increased cortisol your horse might have a weaker immune system than normal. Infections might occur more easily. So regular dental checks, vaccinations and deworming are essential.

- Routine farriery will help to identify early signs of laminitis.

- Give your horse good quality feeding and routinely do weight checks.

- Immediate medical care is needed, like pain relief and foot care, when signs of laminitis occur.

References add