Sudden onset of the inflammatory response, presenting obvious symptoms like clots and thus directly recognizable.

Cattle mastitis

Permanent problems regarding udder health? Caught in the mastitis cost trap? Here you can find useful information to discuss with your veterinarian.

Mastitis is one of the most prevalent health issues in dairy farming with the highest usage of antimicrobials. Mastitis has a major negative impact on cattle welfare, milk quality, enjoyment of the farmer and results in high economic damages.

For mastitis we have a strong focus on precise and effective treatment to facilitate responsible use of antibiotics and to treat only when medically needed. Flexible and convenient applications of our products make it easier and more convenient for vets, farmers and patients. Dechra supports the “One Health” principle. We want to strengthen the position of cattle vets and farmers in combating antimicrobial resistance together with knowledge, practical tools and diagnostic support.

Besides manufacturing high quality modern veterinary medicines we also provide useful tips and tools that you can discuss with your veterinarian.

Our dedicated teams are ready to support you and happy to answer your questions.

What is bovine mastitis?

Mastitis is essentially an inflammation of one or more udder quarters. The local symptoms at the udder level are associated with pain, swelling, redness, and a change in milk appearance (e.g. clots or bloody milk). The disease can be accompanied by symptoms expressed by the entire animal like fever, reluctance to eat, decreased milk yield, and downer cow syndrome (caused by circulatory and/or homeostatic disorders).

Besides major improvements made in animal husbandry and milking technology, udder health is still one of the most prevalent health concerns in dairy farming. Mastitis has a negative impact on cattle welfare and milk quality, but also the enjoyment of the dairy herdsmen and herdswomen.

What causes bovine mastitis?

In general bacterial intramammary infections (IMI) are considered pathogens associated with this disease complex. But mastitis is more complicated than just individual cows getting a bacterial infection. Inflammatory response of the udder can be caused by microorganisms, but also by traumatic or toxic agents or even by inappropriate feeding events. The environment (housing, bedding, climate) and farm management (feeding, milking technique and management of transition-and fresh cow period) play an important role in mastitis at the herd level.

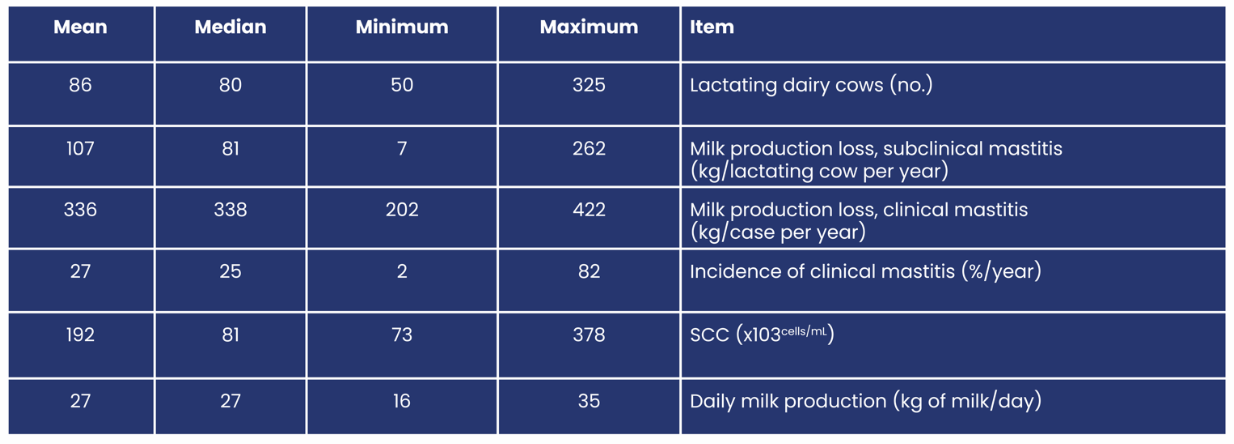

What is the cost of mastitis?

In the Netherlands recently the total economic impact of mastitis was estimated at 240 € per lactating cow per year.1 The direct cost of each case of mastitis is related to treatment costs, like veterinary costs, and medication, but also to discarding of milk due to withdrawal times and food safety concerns.

On top of that indirect costs need to be accounted for, these comprise production loss, extra labour, and culling. Milk loss can be temporary or even permanent. A reasonable (and likely underestimated) loss of about 5% has been proposed for an average clinical case.2 For example this amounts to 375 litres of milk for a cow yielding 8000 kg per year (270 lactation days) if she gets infected within the second month of lactation.

Furthermore, the milk quality can be affected by high somatic cell counts and changes in milk composition, such as the reduction of fat content. A reduction in milk price and fees can be a consequence.

Factored into the 240 € per lactating cow have been costs which were produced by preventive measures trying to limit the frequency of mastitis cases. These cost vary a lot amongst farms which gives the opportunity for veterinarians to improve the financial result of dairy farms with their consulting role.1

Is mastitis in cows contagious?

Mastitis can be a highly contagious condition. Transmission is influenced by many different factors. This depends on the animal, an associated pathogen, but also the animal husbandry situation and the milking process.

An udder can be infected when there is an unbalance between the immunity of the cow and the degree of external infectious pressure. External environment conditions are important factors for risk of mastitis. Weather, hygiene, husbandry and milk techniques are of importance.

How can mastitis be classified?

Depending on the course of the disease and the germs involved, the disease can be classified for a better overview. These classifications are flawed by design, since exceptions to the rule can occur.

Disease:

Acute mastitis add

Chronic mastitis add

Insidious course, few symptoms, often only increased cell counts, economically very alarming due to insidious infection of the entire farm.

One exception to the rule add

Account for mastitis that is not caused by microbes. You might struggle to isolate a “lead” causative pathogen here. This can be due to analytic methods in the laboratory, or sampling method. But it the cause for inflammation might be stress or unbalanced feed as well.

Cause:

Cow-associated microbes add

These bacteria live on the skin of the cows. They are usually well adapted to the cow as a host, so they often trigger a milder kind of inflammations. However, some of these pathogens can cause chronic mastitis with unlikely healing, if they are not treated in a structured regimen.

Environment-associated microbes add

These germs come from the barn environment. They are usually not well adapted to the host, so usually trigger strong inflammations. The good news is that frequent mastitis with environmental pathogens can be prevented by identifying and eliminating hygiene defects.

One exception to the rule add

Some groups of bacteria tend to consist of many different sub-species. For example some Streptococcus uberis or coagulase negative Staphylococci can have properties attributed to both groups.

The strict differentiation between the two groups listed above has been scientifically challenged in the past years.3 Dairy husbandry conditions have undergone drastic change over the last decades, moving from tie on barns to cubicle barns. Hence transmission patterns for bacteria have changed as well rendering some of the existing disease categories outdated.3

What is the difference between clinical mastitis and sub-clinical mastitis?

Sub-clinical mastitis is a condition in the udder without clinical symptoms of the illness and no visible changes in the milk. An increase in somatic cell count might be the only way to identify infected animals.

Sub-clinical cows may show a reduction in milk yield, are at risk for clinical mastitis and are alarming as a source of infections for other cows.

Clinical mastitis describes the condition with visible symptoms to the quarter and / or milk. The milk yield of these animals is reduced most of the time and often not returning to previous levels even after the case of mastitis has been successfully cured.

It can be divided into 3 gradations depending on the severity of the symptoms.

Grade 1 (mild): the milk is abnormal. The milk composition is different, clots might be observed and the color and smell can be different.

Grade 2 (moderate): The milk and udder show visible changes. Udder quarter(s) can be warm, swollen and red. The cow is in pain and can have fever.

Grade 3 (severe): the cow is general sick with fever, shock, dehydration and pain. The udder and milk are changed.

Clinical Mastitis

add

In Grade 1 mastitis, there is a first clinical sign: abnormal milk. The cow is still in good shape.

add

In Grade 2 mastitis, the conditions worsen and there are second clinical signs: the udder is swollen, the cow is in pain.

add

In Grade 3 mastitis, the conditions worsen further: the cow is visibly sick and in pain.

References add

1: van Soest et al. (2016): “Failure and preventive costs of mastitis on Dutch dairy farms”, J. Dairy Sci. 99:8365–8374, doi: 10.3168/jds.2015-10561.

2: Seegers et al. (2003): “Production effects related to mastitis and mastitis economics in dairy cattle herds”, Vet. Res. 34 (2003) 475–491, doi:10.1051/vetres:2003027.

3: Klaas et Zadoks (2018): “An update on environmental mastitis Challenging perceptions”, Transbound Emerg Dis. 2018; 65(1), pp. 166-185. doi: 10.1111/tbed.12704

How to detect mastitis?

Early detection of sub-clinical and clinical mastitis is important to reduce the risk on spreading of the disease amongst the herd, for effective treatment and to take preventive management measurements.

Acute clinical mastitis: add

Acute mastitis is often immediately recognized by the milker by clear symptoms and observation of the individual animals in the milking parlor. Clots in the milk are a sign of cell impairment by inflammatory cells in the udder. In addition, due to swelling of the affected quarters teat, afflicted animals tend to be harder to milk than healthy cows.

Subclinical (chronic) Mastitis: add

Detection of sub-clinical mastitis is more difficult. Sub-clinical infections are often detected via tank- and individual milk data records like the DHI report. High somatic cell count is a sign of risk for clinical mastitis and spreading of infections.

If a farm is not participating in a DHI program, and modern milking equipment is installed, some devices like milking robots can measure the electric conductivity of each cows milk against a threshold. The conductivity of the milk is an early indicator of possible increased SCC and mastitis but not very specific as the increase of conductivity caused by ions can be non-mastitis related.

If neither of the above methods are present at a farm, the only way to identify high risk animals is resorting to the California Mastitis Test (CMT). The Test is cheap and simple, but can be difficult for interpretation and low sensitivity.

Veterinarians, farmers and herdsmen are crucial for successful identification of high risk increased somatic cell count cows. Veterinarians can help with identifying and selection of the suspected cows. Many veterinary clinics and milk analyses labs can have automatic cell counters in place for more accurate and confirmation. Furthermore a lot of veterinary practices offer a regular evaluation of the available data for animal health indicators.

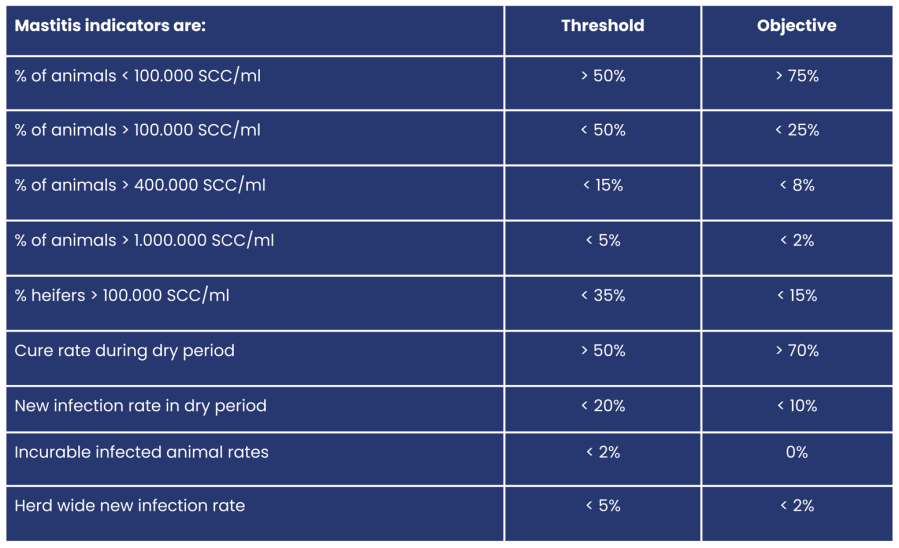

What is high somatic cell count and how to interpretate? add

The somatic cell count (SCC) indicates the number of inflammatory cells in the milk. “Healthy” milk has a low count of inflammatory cells per ml. Nevertheless a certain amount of cells is normal, since their function is providing natural immunity.

The height of the SCC is utilized as an indicator for milk quality and risk of mastitis (see table below). The prevalence of cows with increased cell count indicate a risk of mastitis incidence. Many cow related factors as age, lactation stage, genetics and history are important for analysis. The veterinarian and farmer have important roles to weigh in these factors.

- Regular herd screening, i.e. milk sampling and determination of the significant germs on the farm. Number of samples for herd screening: 10% - 20% of the herd, divided among fresh, lactating and cell count carrier cows.

- For farms with udder health problems or after remediation, it might be helpful to screen the freshly calved cows in order to protect the producing cow herd from pathogen carry over by dry cows / heifers. Practical tip: Weekly pool sample RT-PCR screening from the calf milk taxi. It’s safe to assume most fresh cows after birth are already pooled in the taxi anyway.

What is the role of milk samples for bacteriology?

In acute single cow cases milk samples can be taken from clinical mastitis cows and suspected sub-clinical mastitis cows with clear increased somatic cell count (>400 000 cells/ml).

Bacteriology has several methods in it’s arsenal to identify the causative pathogen / bacteria. Subsequently it can also find out for which antimicrobial the pathogen is sensitive for optimal treatment. In the following you can find a very brief and simplified explanation of the different systems:

Bacterial culture

In a simplified way the milk sample is being processed and put on several selective growth mediums. If a dominant culture grows in one of these mediums, a purified sample is transferred to a suitable broth. After cultivation of the pure culture this sample can be submitted to further biochemical testing.

MALDI TOF

This is a system for mass application and partially automated mass spectrometry. A standard dilution of a purified sample is exposed to a light source. The reflection and absorption pattern of each sample can be measured and attributed specifically to certain pathogens afterwards.

Real time PCR (RT-PCR)

This is a fully automated system. The cells in the sample are being processed and broken up in order to expose the cellular genetic material. Biochemical Markers can bind to known genetic sequences of bacterial strains and identify subspecies. Whilst this method is extremely precise and can even identify microbials in the sample that are already dead or just hard to isolate and grow, it has the downside of not providing a purified sample for susceptibility testing.

The lab analysis through bacterial culture is relatively cheap to perform. Many veterinary clinics also provide this service at the clinic level so the result is faster, the awareness of the role of bacteria grows and treatment and management advice can be shared fast. The MALDI TOF and RT PCR technology require a larger financial investment and may only be available in commercial certified milk labs or very large veterinary clinics.

The role of bacteriology is very important for many reasons:

- Knowing the causative pathogen is the foundation for correct and selective therapy

- Management and husbandry systems can be adjusted according to outcome pathogen.

- A positive bacterial culture outcome is more likely when high SCC cows are early selected and critically targeted for analyse.

How to take a proper milk sample?

For conclusive feedback from the lab it is important that the milk sample is not contaminated with bacteria. This can occur by spilling of faeces, the teat skin, the milkers skin or the environment.

Therefore many tips and instruction protocols are in place to support a correct milk sample technique.

Why is the testing of susceptibility so important?

After a positive bacterial culture, the lab can perform a susceptibility test or ‘antibiogram’ to investigate to which antimicrobials the pathogen is sensitive. This is very important for correct, selective and effective therapy. This becomes even more important due to the resistance development of specific bacteria in human hospitals. We have a critical role in the responsible use of antimicrobials.

- Select prudent use of antibiotics as first-line treatment (Category D, according to EMA categorisation of antibiotics).

- Use results for evaluation and monitoring of treatment grade 2 and 3 mastitis infection.

- Use results to select therapy for grade 1 mastitis and sub-clinical mastitis.

- Find resistant bacteria (β-lactamase producers, MRSA, ESBL, AmpC-producers).

Minimizing antimicrobial usage starts with animal selection. Don’t treat chronic cases with repeated symptoms. Treat fresh infected cows with susceptible pathogens thoroughly instead.

Dechra manufactures high-quality veterinary medicines and we feel the responsibility for the correct use of antimicrobials. Therefore we focus on developing and manufacturing narrow spectrum antimicrobials which minimise the risk of resistance development by specific targeting bacteria. We support veterinarians and farmers with the right and selective choice of therapy.

Dechra developed the “Dechra Paper Ring” which is a susceptibility test with narrow spectrum antibiotics. The ring makes sensitivity testing easier and faster to perform and assists in making precise treatment choices.

The Dechra Paper Ring is a practical tool and makes it easy to perform susceptibility testing in the veterinary clinic. In house bacterial analysis results in fast advice, treatment and follow-up actions rewarded by farmers.

How to treat mastitis in an effective and strategic manner?

The discovery of antibiotic substances and availability of these pharmaceuticals in the second half of the 20th century marked a revolution for veterinary medicine and improvement of milk quality.1 From 1927 to 1956 the connection between different species of bacteria and mastitis were made. The concerns about the disease have been mostly based on implications on public health.2

In the 1960's and -70's several antibiotic therapy regimens were developed, some of these concepts are valid until today.2 Since the 1990's there has been growing awareness towards the issue of development of antimicrobial resistances (AMR) on the example of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Governmental policies have started to address (for example in the Netherlands in the year 2005) a more restrictive use of antimicrobial pharmaceuticals.1

Availability of effective treatment options is paramount for animal welfare concerns. Hence the main objectives of treatment are:

- to cure the current disease

- to restore productivity of the diseased animal

- to avoid relapse

- to prevent infection of other animals

Responsible use of antibiotics means unnecessary or unlikely effective antibiotic treatments should be avoided at all costs. Before starting antibiotic treatment we need to ask ourselves some questions to set our treatment goals:

- How severe is the disease?

- Did this cow already suffer from mastitis during this lactation?

- Is this cow a permanent cell count millionaire?

- How old is this cow?

- Whats the valuation of the afflicted cow?

- Do I know the most common pathogens on my farm (lead mastitis pathogens)?

- Do I have an unusual number of udder infections this month?

Many additional factors need to be considered for optimal treatment choices. Frequent consultations with your prescribing vet can assist to weigh the different factors. The choice on treatment intensity depends on factors related to the cow, the pathogen and availability of active substances and should be made based on the probability of successful cure.

A combined antibiotic treatment (local and systemic) can be considered with high prevalence of high SCC. Systemic treatment lowers cow SCC.3 The bacterial cure rate of many gram positive bacteria increase with a combined treatment.4

Available active substances for ruminant veterinary medicine define the following approaches for successful mastitis therapy:

Available active substances for ruminant veterinary medicine define the following approaches for successful mastitis therapy:

Pain alleviation add

Udder inflammations are painful due to milk congestion. Cows afflicted with mastitis usually are harder to milk than healthy cows due to the inflammatory response. In mastitis therapeutics, there is a growing awareness of the importance of the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in cattle. Benefits include reduced inflammation and mediating endotoxin-induced effects.6

Even a single dose early administration of an effective anti-inflammatory drug increases the likelihood of recovery.5 This therapeutic approach results in a lower somatic cell count, less milk loss, better clinical result and survival rates. And improved fertility after mastitis case.7,8

Suitable antibiotic add

Talk to your veterinarian about selecting a suitable antibiotic. Cephalosporins, or so-called gyrase inhibitors, are highly effective agents, but should not be used as the first choice for mild cases. Effective alternatives are available.

Especially in mastitis cases where cows are freshly infected, it may be useful to not only treat the cow with intramammary teat tubes but also via an injection. The treatment success rate increases significantly for some cow-associated bacteria pathogens.4

To avoid antibiotic resistance, the selection of a suitable active ingredient, the correct dosage, and a treatment duration of at least 3 days is extremely important.

Puncture vials with rubber stoppers (usually indicated for systemic therapy e.g. via injection) should never be used for intramammary application even with a single-use syringe. These products are often not formulated for intramammary use and commercial intramammary injectors are used under adjusted quality control standards to ensure safety for the animal, but also in regards to the appropriate withdrawal periods after the complete treatment.

Circulation treatment add

If the cow's circulation is disturbed (eats little, has hollow eyes and gets up only tediously or not at all), contact your veterinarian urgently. There are other treatment options to stabilize the animal's circulation by intravenous infusion of fluids and minerals.

E. coli mastitis, a lost cause or not?

In practice, the term E. coli mastitis has been used synonymously with severe acute mastitis cases. But since a multitude of pathogens can induce these severe symptoms in the udder quarter and the animal itself, you cannot deduce that Escherichia coli caused this mastitis case. Other bacteria like Klebsiella spp., or S. aureus can produce similar symptoms to E. coli.12,14 Only bacteriology can show the underlying pathogen causing the disease with certainty.

Nevertheless, these animals are often in life-threatening conditions and require urgent attention. The treatment results for severe mastitis have varied outcomes. The truth is that grade 3 mastitis can be a life-endangering disease for the animal, mostly due to septicemia and/or an immunogenic shock. Several publications have shown the average treatment success rate and likeliness of recovery to production at about 75%.4,9

Most interestingly these percentages do not seem to differ a lot in between the intensity of antibiotic treatment.4,9 Furthermore publications show that using active substances that distribute hardly into the mammary gland is linked to increased survival rates.10 These findings indicate that septicemia, toxemia, and cardiovascular symptoms need to be addressed first. There is no support the use of broad-spectrum intramammary antimicrobial treatment in cases of mild or moderate E. coli mastitis is neccessary.11

Identify the first signs of E. Coli Mastitis

In the case of severe acute E. coli mastitis, the cow weakens considerably and rapidly. For the farmer, herdswoman, or herdsman the challenge is to pick up the first signs of a worsened condition and take immediate action. In half an hour, a cow can transform from 'just not fully fit' into a sick cow with a fever of > 40 degrees Celsius and severe hardness of the infected udder quarter. Subsequently, the cow can quickly worsen. The earlier in the course of the disease, a sick cow is treated, the greater the chance of recovery. It is therefore important for farmers, herdswoman, or herdsmen to know their cows well, in order to notice abnormal behaviour more rapidly.

How to tackle E. coli Mastitis?

In the case of severe symptoms, treatment can be started according to the treatment plan and available documentation. However, if coliform bacteria die, endotoxin is released from the bacterial cell wall which causes many of the symptoms we see in the cow, possibly even causing shock.13

Mastitis-related virulence factors for strains of coliform bacteria are the ability to utilize lactose as an energy source and the ability to survive in near anaerobic conditions.13 These abilities are correlated to the conditions in mammary gland secretion and allow for shorter multiplication times. The migration of coliform bacteria into the circulation (septicemia) can occur on rare occasions since the blood-milk barrier is destroyed.13 In the incidence of septicemia the prognosis for the animal is significantly worse. All the above are reasons why rapid action and providing optimal support, are critical to recovery.

The migration of coliform bacteria into the circulation (septicemia) can occur on rare occasions since the blood-milk barrier is destroyed.13 In the incidence of septicemia the prognosis for the animal is significantly worse.

All the above are reasons why rapid action and providing optimal support, are critical to recovery.

Restore fluid balance add

In order to swiftly correct dehydration, the veterinarian can administer a high concentrated (hypertonic) intravenous infusion. This is an emergency measure drawing a lot of water into the circular system. Cows submitted to this therapeutic approach should drink a lot of water afterwards. This can also be supported by oral fluid therapy.11 The extra fluids allow toxins to be removed from the body more quickly.

Rumen support add

The unique organ influencing bovine metabolism is the rumen. Retaining ruminal function ensures feed intake and a swift recovery.

A rumen supporting bolus or ruminal starters contains live yeasts and supports a healthy rumen flora and fermentation. Buffers like Sodium- or potassium carbonate can assist in stabilising ruminal pH in case of ruminal atony. Amino acids and vitamins stimulate metabolism and support the liver in the formation of glucose.

Painkillers and anti-inflammatory drugs add

Not only can these drugs help alleviate some of the immunogenic shock symptoms, but also they can make the cow feel better, so it will resume feed and water intake faster. This benefits the recovery of the cow, which is reflected in lower inflammation signs (e.g. SCC, body temperature), higher rumen motility and lower likelihood of culling.5,11

So with the next serious mastitis: take on the challenge and work towards recovery!

Preventing E. coli mastitis

As the name suggests, environmental associated bacteria are rarely contagious, they come from the cows direct environment. If E. coli and so-called “coliform bacteria” are the mastitis lead pathogen on your farm, a veterinarian can help look for likely sources of infection.

Instead of thinking in fixed patterns, a farm individual approach is mandatory. Understanding bacterial transmission and infectious links help identify every farm’s specific bottleneck. Small changes in the local hygiene management can often lead to significant improvements in the situation.

Critical hygiene points to limit environmental mastitis are: add

- Bedding material: In general anorganic bedding material (sand or limestone) proves to be less likely to carry high load of bacteria than cellulose based material (sawdust, straw or manure).13

- Regular renewal of the bedding surface.

- Storage and source of bedding material.

- Cow-appropriate cubicle size prevents teat trauma and improves lying behaviour.

- Cleanliness of cows.

- Remove udder fur.

- Reduce heat stress.

- Adjusted nutrition, especially in the dry period.

- Dry cow and transition cow management – Subclinical IMI can occur in the dry period and break out in the early lactation phase.14

- Teat dip and dipping equipment.

- Manure removal.

Authors

By Matthias Riedel Mag. med. vet.

Business Manager for Cattle and Vaccines

Dechra Veterinary Products

By Aleksandra Krawczyk DVM

Product Manager FAP / Technical Manager Cattle

Dechra Veterinary Products

References add

- D. C. Speksnijder et al., 2014: “Reduction of Veterinary Antimicrobial Use in the Netherlands. The Dutch Success Model.”; Zoonoses and Public Health 62(1), pp: 79–87.

- P. L. Ruegg, 2017: “A 100-Year Review: Mastitis detection, management, and prevention”; J. Dairy Sci. 100(12), pp: 10381–10397. doi: 10.3168/jds.2017-13023

- Sérieys et al., 2005: “Comparative efficacy of local and systemic antibiotic treatment in lactating cows with clinical mastitis”; J Dairy Sci. 88(1), pp: 93-9. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(05)72666-7

- Steeneveld et al., 2011: “Cow-specific treatment of clinical mastitis: an economic approach.” J dairy Science; Jan;94(1): 174-88. doi: 10.3168/jds.2010-3367

- McDougall et al, 2009: “Effect of treatment with the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory meloxicam on milk production, somatic cell count, probability of re-treatment, and culling of dairy cows with mild clinical mastitis. J. Dairy Sci. 92:4421–4431.

- James Breen, 2017: “The importance of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in mastitis therapeutics”; Livestock; 22(4), pp. 182–18. doi: 10.12968/live.2017.22.4.182

- McDougall et al., 2016: “Addition of meloxicam to the treatment of clinical mastitis improves subsequent reproductive performance.” J. Dairy Sci. 2016: 99; pp: 2026-2042; doi: 10.3168/jds.2015-9615

- Felix J. S. van Soes et al., 2018: “Addition of meloxicam to the treatment of bovine clinical mastitis results in a net economic benefit to the dairy farmer.” J. Dairy Sci. 101(4), pp. 3387–3397; doi: 10.3168/jds.2017-12869

- L.Sujola et al., 2010 Efficacy of enrofloxacin in the treatment of naturally occurring acute clinical Escherichia coli mastitis; J. Dairy Sci. 93 :1960–1969, doi: 10.3168/jds.2009-2462.

- R. J. Erskine et al., 2002 Efficacy of Systemic Ceftiofur as a Therapy for Severe Clinical Mastitis in Dairy Cattle; J. Dairy Sci. 85(10):2571-5, doi: 85(10):2571-5

- Sujola et al., 2013: “Treatment for bovine Escherichia coli mastitis – an evidence-based approach”; J. vet. Pharmacol. Therap. doi: 10.1111/jvp.12057

- R. G. M. Olde Riekerink et al., 2008: “Incidence Rate of Clinical Mastitis on Canadian Dairy Farms”, J. Dairy Sci. 91, pp: 1366–1377. doi:10.3168/jds.2007-0757

- J. Hogan, K. L. Smith, 2003: “Coliform mastitis”, Vet. Res. 34, pp: 507–519. doi: 10.1051/vetres:200302

- Klaas et Zadoks, 2018: “An update on environmental mastitis: Challenging perceptions”, Transbound Emerg Dis. 2018; 65(1), pp. 166-185. doi: 10.1111/tbed.12704